The hidden cost of plastic in healthcare

“I just want to say one word to you, just one word - plastics. There’s a great future in plastics.” These words voiced by the fictional character, Mr McGuire in the 1967 film, The Graduate, were truly prophetic as since 1950, plastic production has increased by a factor of 230 from 2 to 460 million tonnes per year. Whilst plastic has enabled innovation in many industries including healthcare, this has come at an environmental and social cost which cannot be ignored. 98% of plastic is derived from fossil fuels, the industry produces 2 billion tonnes of CO2 per year and almost 40% of products are intended for single use. Compared to today, production is predicted to double by 2040, triple by 2060 and we can neither get to ‘net zero’ nor restore the planet to good health without considering plastic.

Fossil fuel plastic

causes death,

disability, and disease at every stage of its lifecycle; impacting upon the

health of the planet

and the many species, including humans, which call it home. Plastic is

comprised of complex polymers and thousands of chemicals which can be

persistent, bio accumulative and toxic including endocrine disrupters, a particular

concern for the food and medical industries. Plastic is designed to be durable

and in 2018, it was reported that 6.3

of the 8.3 billion tonnes produced persists as waste in landfill or the

environment. Human health impacts are predominantly experienced by those in

lower Human Development Index countries, fence line communities, the vulnerable

and extremes of age.

Healthcare organisations

must be cognizant of their footprint; otherwise, the products and services procured

and used with good intention will, through contributing to climate change and

environmental ill health, fuel further demand for services at a time when they

themselves are trying to reduce their own environmental impact. It is therefore

welcome to see the NHS

Standard Contract requiring action to be taken by the whole value chain to

reduce the avoidable use of single use plastic which comprises 23%

of the waste produced by the NHS, most of which is ultimately incinerated

whether it sees clinical action or not.

The UNEP

Global Plastic Treaty aims to ‘turn off the tap’ on single-use plastics and

whilst healthcare may fall into the category of ‘essential

use’, we must still aim to first, do least harm by reducing

use whenever possible. Despite innovations in material science, bioplastic,

reduction in medical device plastic mass, use of less-toxic polymers, reintroduction

of reuseable products and recycling, we must be honest that for the foreseeable

future, healthcare will remain dependent on many single-use plastic products.

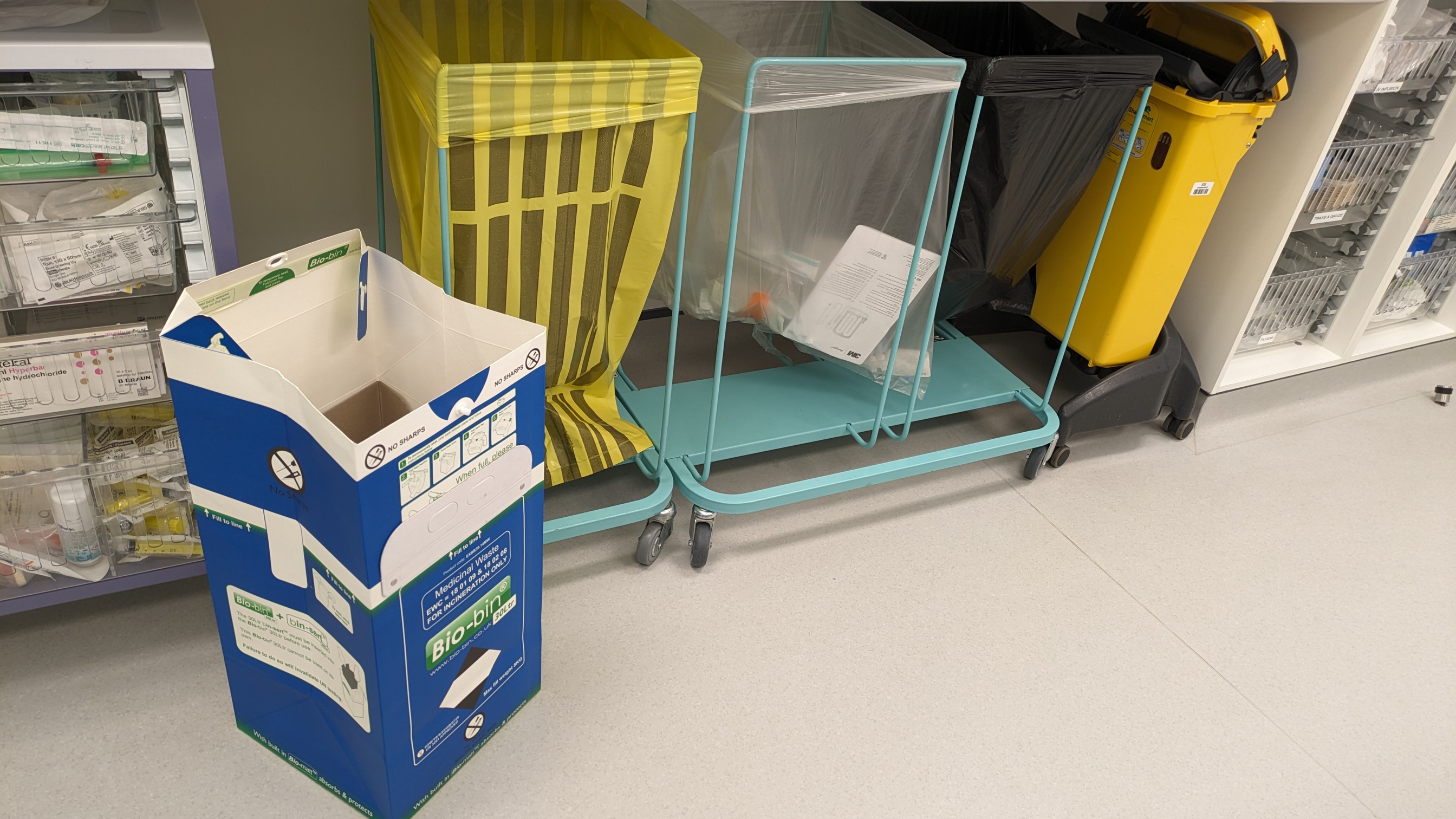

One of the most

important decisions a healthcare professional can make is when to open the

packaging of a single-use device as once opened, the item becomes waste whether

used or not. It’s therefore essential to move from a ‘just in case’ to a ‘confirmed

required’ mindset. Staff responsible for preparing clinical areas like

anaesthetic rooms must check the requirements of anaesthetists before items are

opened. An equally important decision is how to dispose of used items safely with

the least environmental harm. Healthcare waste is deemed non-hazardous until

proven or suspected otherwise and appropriate containers must therefore be available

to accommodate all potential waste types for the specific clinical area.

Safe

and sustainable management of healthcare waste provides clear guidance and its

essential clinical, sustainability and waste management leads create supporting

materials to help staff segregate waste correctly. Ensuring waste is disposed

through the correct waste stream using the most sustainable containers has a significant,

measurable impact on the amount of plastic consumed, distance transported,

method of treatment, whether the energy created can be utilised by the national

grid and cost.

Mapping these pathways

and calculating metrics for our different waste streams led to several changes.

By moving to Sharpsmart reuseable

sharps bins, our 11-bedded critical care unit reduced the amount of (single-use

sharp bin) plastic incinerated by 2.3 tonnes per year and through introducing blue Bio-bin containers into every bedspace,

redirected 6.4 tonnes of medicinal waste (predominantly used fluid bags,

syringes and giving sets) to the less environmentally harmful, non-hazardous waste

stream.

This waste

redirection followed an analysis of Health

and Safety Executive Regulations, a local risk assessment and agreement the

risk to staff from a giving set ‘spike’ which remained embedded in an

intravenous bag was minimal. We communicated that all giving sets along with

their attached bags of intravenous fluids/residual pharmaceuticals could be

disposed of in Bio-bins and since making this change several years ago, no

associated injuries have been reported. The only pharmaceuticals not disposed through

the blue waste stream are those with cytotoxic or cytostatic properties, hazardous

sharps, or items contaminated during use. These are placed in the purple or yellow

sharp waste streams respectively.

This ‘balance of

probabilities’ approach to theoretical harm from a shielded giving set

spike compared to the known increased environmental harm from overly

cautious classification of healthcare waste as hazardous is a great example of

a pragmatic approach to sustainability. Challenging existing processes which we

continue to do because we’ve “always done it that way” is essential when plotting

a path to truly sustainable healthcare. Concerns over the space required for these

additional waste containers were quickly allayed by the positive feeling arising

from a visible reduction of the environmental impact of care. Demands on staff

time reduced through fewer container exchanges and cost savings amounted to

thousands from just one clinical area.

Reducing the demand

pull for single-use items can be challenging if the infrastructure to support the

re-introduction of reuseable devices has changed and whilst supporting and pursuing

the principles of circularity, it’s essential to consider service demands and

patient needs. For example, a reuseable bronchoscope on critical care is of

little value when in transit for cleaning or being repaired which in our

experience, can take weeks. Every additional day a patient spends on the unit comes

with an energy, plastic,

drug and pollution cost; factors not always included in product life

cycle assessments. Our approach is therefore to ensure continued

availability of single

patient use bronchoscopes and to support environmentally-ambitious

companies in making devices as sustainable as possible.

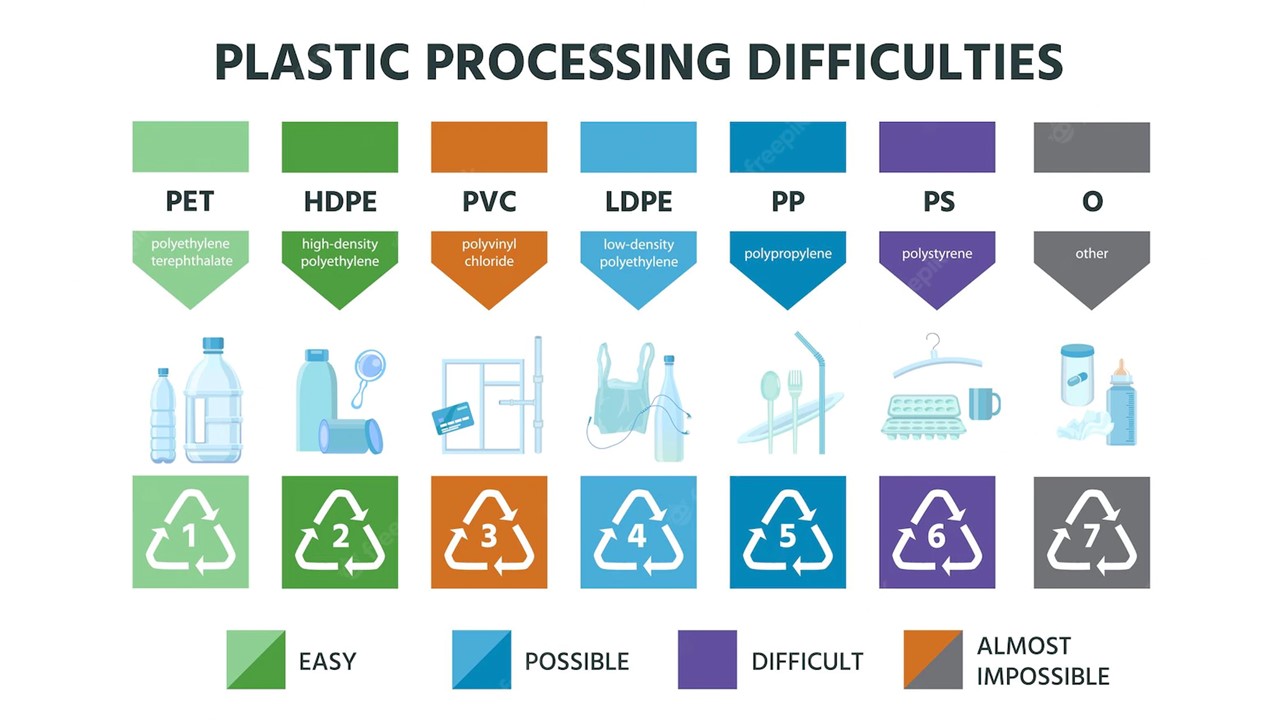

Despite the use

of composite materials and distinct lack of clues on packaging, we continue to

separate plastic from paper never sure what can or will be recycled. Whilst

items contaminated with a body fluid will primarily be directed toward the

offensive waste stream (tiger bin), questions are often asked of why we do not

recycle non-hazardous plastic waste. Is there evidence this poses a higher risk

than a random plastic drinks bottle destined for recycling following a beach

clean? As material complexity may currently preclude this pathway, future

products and packaging must be designed to be reused, recycled or disposed of

with minimal environmental impact whilst as an industry, we must be pragmatic

about risk.

My personal journey

exploring healthcare plastic and waste has thrown up all sorts of emotions.

Plastic is simultaneously harmful and beneficial, but with the benefits received

by those in countries with accessible healthcare system and the harms

externalised to the planet and those less fortunate. With the increased

knowledge we now possess, we should at least acknowledge the harm, use products

responsibly, communicate why, educate our peers and first, do least harm

whenever possible.

Everyone has an equal right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health and from a climate and environmental perspective, health is everything; it’s why we care. The trusted voices of healthcare professionals can, as we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic, cut through the noise and by including climate, environment and their impacts on health within our own professional development, we can become effective communicators inspiring others to act both in their personal and professional lives.

Richard Hixson.

Related Articles

How can I reduce my use of plastic in healthcare?

Fossil fuel plastic causes death, disability, and disease at every stage of its lifecycle; impacting upon the health of the planet and the many species which call it home. Whilst the global plastics treaty is taking shape, healthcare professionals can act now to reduce their own impact and educate others.

Written 08.05.2024

View Article

Climate and Environmental Literacy on CPDmatch

Why we need collaboration to improve climate and environmental literacy.

Written 23.11.2024

View Article

Achieving high staff engagement with net zero education and training in the NHS

The Delivering a net zero NHS statutory guidance, recognises that an upskilled workforce will be needed to drive and implement net zero initiatives. They will need to be supported to learn, innovate and embed sustainable development into everyday actions in the health service. This is how one UK Trust achieved high compliance in net zero training.

Written 03.08.2024

View Article

Aethic and the fight against Greenwashing: “reef safe” claims

Sun protection is essential, but with growing awareness about environmental impact, choosing the right sunscreen can feel overwhelming. Unfortunately, some brands exploit this concern with "greenwashing".

Written 25.05.2024

View Article

CPDmatch FAQs

The following Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) are written with healthcare professionals in mind although many of the principles will be relevant to other professions. Please contact us if you have any comments or specific questions you’d like us to answer.

Written 03.06.2024

View Article